This flash essay is part of a collaborative, constrained-writing challenge undertaken by some members of the Bangalore Substack Writers’ Group. This month, each of us examined the concept of ‘LANGUAGE’. At the bottom of this snippet, you’ll find links to other essays by fellow writers.

I recently made my podcast debut, as one inevitably does nowadays. I was invited to discuss dreams, a subject I’ve written about with some seriousness over the years. Unfortunately, it wasn’t quite the experience I’d hoped for, because the channel caters to a predominantly Hindi-speaking audience. Within the cultural echo chamber of a solitary language, the nebulous terrain of nightly dreams veers towards the occult. What is simply to be felt in a dream begins to be feared. The hosts, seemingly unaware of the nuance, dismissed my concern. “Don’t overthink it,” they said. “Just speak like you do at home.”

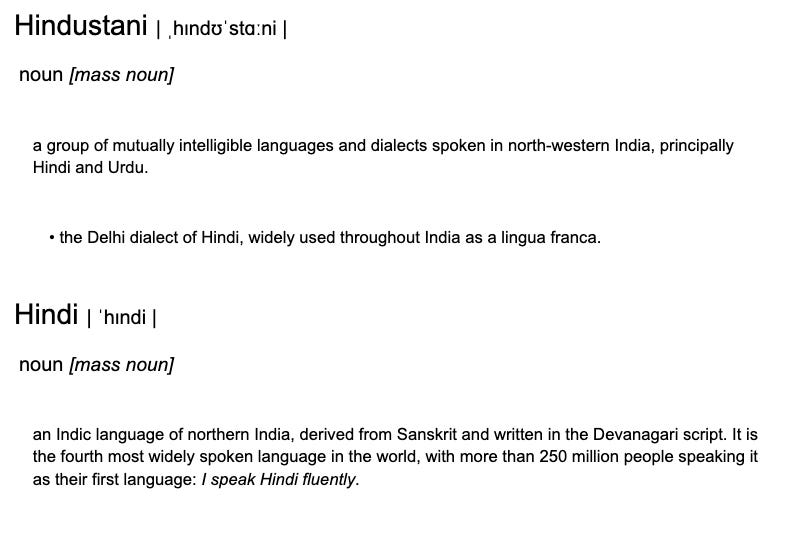

Like many Indians of a certain socio-economic class, I grew up comfortably bilingual. But, unlike most, I didn’t reserve one language for the home and the other for the world. I spoke both languages at home: English with my mother, Hindustani with my father. Each tongue sounded like the parent it belonged to, its syntax changing over the years. At the age of eight, I was introduced to a third language. Français was a chic, first-worldly addition to the repertoire. Among the three, English remained the language I returned to.

In the milieu of Delhi, fluency in English signals a kind of privilege that ostensible wealth can never match. My command of English has often preceded me in rooms, inviting awe and disdain in equal measure. My neglected, imperfect Hindi, on the other hand, has always been indulged. Fumbles are forgivable, even “cute”.

My problem with Hindi was never about proficiency. Hindi is an intimate language. Tu, tum, aap (three ways to say “you”) – Hindi insists on defining the dyad. English allows for distance. With strangers, I prefer English. But the access to English has never been equal. And so, when I speak Hindi, I hold back, unwilling to share its intimacy with just anyone.

~

As an early adopter of social media, I was quickly acquainted with the performativity of language on the Internet. I remember agonising over the “About Me” section of hi5 and MySpace. There are few undertakings more perversely narcissistic than having to describe yourself for an audience (and yet, more subtly, I do just that in these personal essays!). I reached for the most ornate adjectives I could find. A friend with a proclivity for puns bestowed on me the fond title of “Rictionary”. My first-ever troll commented, “English toh aise bolti hai jaise maa-baap England se hain (You’d think her parents were British, the way she speaks English)”. My way with words had become a proxy for my intellect, and, dare I admit, for my sense of self.

~

When I was five, my parents decided I was going to the wrong school, and I was made to switch. Let’s, rather unimaginatively, call the two schools A and B. In moving from School A to School B, I went from being a chatty child, gently reprimanded for having too much to say, to becoming unrecognisably silent, bearing the cross of the “quiet” child. School B had styled itself as the pinnacle of post-colonial aspiration; students were berated for letting slip even a word of Hindi. Watching my classmates struggle with words for sundries like box and bottle in English, I concealed my fluency. On the rare occasion that I was asked to speak, I would pretend to fumble, a miserable attempt at fitting in. My silence is what my old classmates still remember me by. Even so, in forgetting how to speak, I learnt to write.

~

On the periphery of everyday exchanges, there’s a cacophony of unfamiliar lilts. My partner’s family speaks Telugu, Bangalore insists on Kannada, and inside my phone lives a nearly-1900 day Duolingo streak for French. I may think, write, and dream in English, but my favourite language is the one that my dog understands. It’s the best one, for it has no need for tenses – no past, no future, only the comfort of now.

Essays by fellow writers:

Loss of a language By Rakhi Anil, Rakhi’s Substack

Beyond Words and Dialects by Aarti Krishnakumar, Aarti’s Substack

In search of my lost mother tongue by Siddhesh Raut, Shana, Ded Shana

The language question by Rahul Singh, Mehfil

Geography & Language by Devayani Khare, Geosophy

The Dance of Languages by Haridas Jayakumar, Harry

Poetic Silence - From Anand Bhavan to 3039 and back by Amit Charles, @acnotes

No Garam Aloo in Tamil Nadu by Ayush, Ayush's Substack

Lost in translation by Vikram, Vikram’s Substack

I’ve been thinking a lot about tongues, again. by Ameya, (Always) Ameya

The Language Beneath Words by Mihir Chate, Mihir's Substack

What does this mean? by Nidhishree Venugopal, General in her Labyrinth

The Language of Murder by Gowri N Kishore | About Murder, She Wrote.

Jal-Elephants, Thread-Navels, and Other Sanskrit Beasts by Rajat Gururaj, I came, I saw, I Floundered

Of Language, Love and Longing: Politics, Mother Tongue and Loss by Aryan Kavan Gowda, Wonderings of a Wanderer

The Bengaluru Blend by Avinash Shenoy, Off the walls

An Ode to Languages, by Lavina G, The Nexus Terrain

Thanks for penning this thoughtful, thought-provoking piece. I never really thought of the performativity of language on the internet. Oddly, in this AI age, mistakes seem to make us fit in better, echoing your fumbles in the new school. Here's to more such essays that bridge the language of the heart, with the language of words!

I love the idea of having a secret language with your dog. I've never thought of it like that, perhaps because I've never had a pet, but that seems like a really special thing to share!